Key to remember:

I need leave to care for my pregnant wife’ was enough FMLA notice

Court allows case to proceed

Teryl was a freight handler loading and unloading trailers from 5:30 p.m. to 2:30 a.m. Before clocking out at the end of the shift, freight handlers had to check with the dock supervisor to make sure no other trailers required loading or unloading. If there were still trailers that needed to be unloaded at the end of the shift, freight handlers were expected to work overtime.

In March, Teryl announced that his wife was pregnant. Shortly afterward, he asked Rickey, a manager, about taking time off under the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) in case he needed it for his wife’s pregnancy. Rickey told James he was “moving too fast” and that he didn’t need to ask about leave until after the child was born.

In June, the pregnancy was deemed “high risk,” and she could no longer drive, so Teryl needed to care for her as much as possible. Teryl told his supervisors that there would be times he had to leave early or miss days to care for his wife. No one told Teryl of his FMLA rights.

On June 25, Teryl told a supervisor that he had to leave at the end of his shift to ensure his wife was okay and drive her to an appointment. After finishing his shift, he was leaving work for the day when a supervisor stopped him and told him he had to work overtime. Teryl refused to stay. Management recorded the incident as his refusal to work overtime when needed.

On July 1, throughout his shift, his wife was giving him updates on the pain she was experiencing and her fear that something was wrong with her pregnancy. At the end of his shift, Teryl clocked out and began to leave the worksite. A manager stopped him, telling him that if he left, it would be considered job abandonment. Teryl left. The next day, Rickey requested Teryl’s termination.

On July 2, Teryl took his wife to the hospital. The pregnancy was in such a dangerous state that the baby had to be delivered immediately — two and a half months early. After the baby was born, Teryl applied for and received paid parental leave from July 6-17.

On July 20, Teryl submitted FMLA paperwork for additional leave, which the employer later approved. A couple of days later, the employer terminated Teryl.

Teryl sued, claiming that the employer interfered with his FMLA rights. The employer asked that the case be thrown out; that Teryl didn’t give notice of the need for leave. The court disagreed with the employer.

The court held that a jury could find that Teryl was fired from his job as a direct result of leaving after completing his shift to care for his wife, and he had given enough notice.

James v. FedEx Freight, Inc., 11th Circuit Court of Appeals, No. 24-12907, November 7, 2025

Once an employee puts their employer on notice of the need for leave, which supervisors must recognize, employers have 5 business days to give employees an eligibility notice.

This article was written by Darlene M. Clabault, SHRM-CP, PHR, CLMS, of J. J. Keller & Associates, Inc. The content of these news items, in whole or in part, MAY NOT be copied into any other uses without consulting the originator of the content.

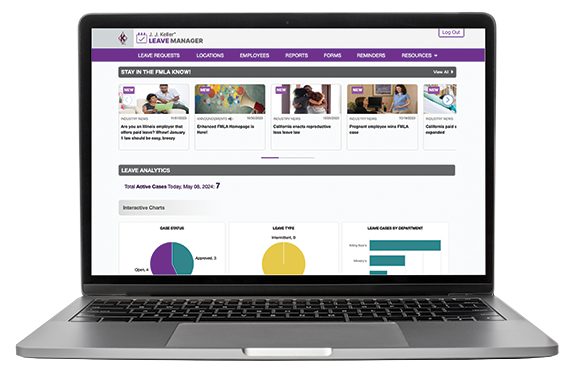

The J. J. Keller LEAVE MANAGER service is your business resource for tracking employee leave and ensuring compliance with the latest Federal and State FMLA and leave requirements.